The 'Just-In-Case' Feature Graveyard: Why I'm Finally Learning to Say No to Over-Engineering

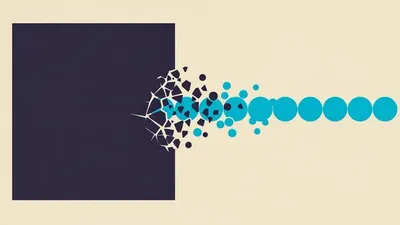

An honest look at the seductive trap of building for hypothetical future requirements and how I started prioritizing 'Now' over 'Maybe.'

I was digging through a legacy repository last night. Not for work, mind you—I was just looking for a specific regex I remembered writing back in 2021. What I found instead was a monument to my own hubris.

It was a NotificationService. Simple enough, right? Except it wasn't. It featured a complex provider-agnostic strategy pattern, a multi-layered queueing system with priority weights, and a "plugin architecture" for third-party integrations that didn't exist yet.

The kicker? Three years later, that service still only sends basic emails via SendGrid.

All those abstractions, those generic interfaces, and that "flexible" architecture? It’s just sitting there. Dead weight. A graveyard of "just-in-case" features that added complexity, slowed down every subsequent PR, and ultimately solved problems that never actually materialized.

Honestly, it was embarrassing.

The Seductive Call of "What If?"

As developers, we are trained to think about edge cases. It’s literally our job. We think about what happens if the database goes down, if the user enters a negative number, or if the API returns a 503.

But there’s a dangerous mutation of this mindset that I call "Speculative Engineering." It’s when we start asking "What if?" about business requirements rather than technical stability.

- _"What if we want to switch from PostgreSQL to MongoDB next month?"_ (You won't.)

- _"What if the client wants to support 15 different payment gateways instead of just Stripe?"_ (They don't have the budget for that anyway.)

- _"What if we need to scale to ten million users by Tuesday?"_ (You currently have twelve.)

We tell ourselves we're being "proactive." We tell our managers we're building "extensible" systems. But let’s be real: usually, we’re just bored and want to play with a complex pattern we saw in a blog post. I know I was.

The Abstraction Tax

Every time you add a layer of abstraction to account for a future requirement, you pay a tax.

It’s not just the time it takes to write that code. It’s the cognitive load for every developer who touches that file after you. It’s the extra hops you have to jump through during debugging. It's the "where is this actually implemented?" dance you have to do in your IDE because everything is hidden behind three interfaces and a factory.

Look at this. This is roughly what my 2021 self thought was "good, scalable code" for a simple user preference update:

// The Over-Engineered Approach

interface IPreferenceStrategy {

update(userId: string, data: any): Promise<void>

}

class DatabasePreferenceStrategy implements IPreferenceStrategy {

async update(userId: string, data: any) {

// ... logic

}

}

class PreferenceService {

private strategy: IPreferenceStrategy

constructor(strategy: IPreferenceStrategy) {

this.strategy = strategy

}

async execute(userId: string, data: any) {

return this.strategy.update(userId, data)

}

}

// In the actual route...

const service = new PreferenceService(new DatabasePreferenceStrategy())

await service.execute(user.id, { theme: 'dark' })And here is what I should have written:

// The "Now" Approach

async function updateTheme(userId: string, theme: 'light' | 'dark') {

return await db.user.update({

where: { id: userId },

data: { theme },

})

}The second one is boring. It’s direct. It’s also incredibly easy to test, easy to read, and—this is the important part—easy to delete or refactor if the requirements actually change.

The first version is a nightmare to change because you’ve already committed to a specific "strategy" mental model. If the requirements shift in a way that doesn't fit a strategy pattern, you're stuck trying to jam a square peg into a generic hole.

<Callout> Complexity is a one-way street. It is infinitely easier to add an abstraction when you finally need it than it is to strip one out once it’s woven into your business logic. </Callout>

The "I'll Just Add One More Flag" Trap

Over-engineering doesn't always look like complex patterns. Sometimes it looks like "The God Function."

You know the one. It starts as fetchData(). Then it becomes fetchData(includeDeleted). Then fetchData(includeDeleted, sortOrder, limit, offset, useCache, forceRefresh, returnRawResponse).

We do this because we're afraid of duplicating code. We’ve had "DRY" (Don't Repeat Yourself) beaten into our heads since day one. But here’s a hot take: Duplication is far cheaper than the wrong abstraction.

I’ve spent hours trying to untangle a single function that handled four different "similar" use cases with a mess of if/else logic. If the author had just written four separate, simple functions, I could have fixed the bug in five minutes.

Why We Struggle to Say No

It took me a long time to realize why I kept falling into this trap. It wasn't just about being a "good" engineer.

- Fear of being "wrong": We think that if we have to change our code later, it means we failed the first time. In reality, changing code to meet evolving needs is the definition of successful software.

- The Shiny Object Syndrome: New patterns, new libraries, and complex architectures are fun. CRUD is not.

- Intellectual Validation: Writing a complex, generic system makes us feel smart. Writing a simple

ifstatement feels like something a junior could do.

But guess what? The most senior engineers I know are the ones who write code that looks "easy." They’re the ones who fight to keep the codebase small and boring.

Learning to Love the "Now"

These days, I have a new rule: Build for the requirements you have, not the ones you’re afraid of.

If a stakeholder says, "We might want to add X in the future," I say, "Great, we'll build the foundation for that when we're ready to start work on X."

This doesn't mean writing _bad_ code. It means writing _focused_ code. It means:

- Using concrete types instead of generics until you have at least three different types to handle.

- Keeping logic in the most obvious place, even if it feels "too simple."

- Writing tests for the behavior, not the implementation, so you can refactor safely later.

The funny thing is, since I stopped trying to predict the future, I’m actually shipping faster. My PRs are smaller. My code reviews are shorter. And weirdly enough, when the requirements _do_ change (and they always do), the code is so simple that changing it is a breeze.

The Challenge

Next time you’re about to create a new interface "just in case" you need to swap out an implementation, or you’re about to add a fifth optional parameter to a function to handle a "potential" use case—stop.

Take a breath. Ask yourself: "Am I solving a problem that exists right now?"

If the answer is no, delete it. Your future self will thank you for not leaving them another grave to tend to.

To be honest, it’s a relief. There’s a certain zen in realizing that you don't have to be a psychic to be a good developer. You just have to be a good listener to the problems of today.

Anyway, I'm going back to that old repo. I think I've got some "flexible" plugins to delete. Turns out, I don't need them. I never did.