The Ghost in the Second Tab: How I Finally Solved Browser Concurrency with Web Locks

Stop letting your browser tabs fight over the same data and start using proper resource locking to handle concurrency like a pro.

You’ve probably been told that JavaScript is single-threaded and therefore immune to the classic race conditions that plague languages like C++ or Java. This is a lie. While a single execution context (a tab or a worker) runs on a single thread, your *application* often exists across multiple tabs, windows, and workers. The moment you open that second tab, your "single-threaded" world becomes a distributed system.

I learned this the hard way while building a local-first task manager. I was using IndexedDB for storage and a simple background sync process. Everything worked perfectly until I opened the app in two windows. Suddenly, I had "ghost" data appearing. Tasks would duplicate, or worse, one tab would overwrite the state of the other because they were both trying to perform a "cleanup" routine at the exact same time.

We usually try to solve this with storage events or BroadcastChannel, but those are reactive. They tell you something *happened*. They don't help you coordinate something *about to happen*. To stop the ghosts, you don't need better events; you need the Web Locks API.

The Problem: The Invisible Collision

Imagine a scenario where your app needs to refresh an OAuth token. The token expires, and the user has four tabs open. All four tabs detect the expiration at the same millisecond.

If you aren't careful, all four tabs will fire a request to your /refresh endpoint. Your server might invalidate the previous refresh token after the first call, causing the other three requests to fail and log the user out. You've just created a terrible user experience because your tabs couldn't talk to each other about who was "in charge."

Before Web Locks, we used localStorage as a makeshift mutex. We’d write localStorage.setItem('is_syncing', 'true'), but that's inherently broken. localStorage is synchronous, but it isn't atomic across processes. Two tabs can check the value, see it’s null, and both write true simultaneously.

Enter the Web Locks API

The Web Locks API (navigator.locks) is a surprisingly simple tool that allows you to manage resource contention across different tabs, windows, and workers sharing the same origin. It’s built into the browser and handles the messy business of "who got here first" with platform-level precision.

The syntax looks like this:

await navigator.locks.request('my_resource_lock', async (lock) => {

// I hold the lock now.

// Any other tab requesting 'my_resource_lock' will wait until

// this async function completes.

await doSensitiveWork();

});The browser manages a queue. If Tab A holds the lock, Tab B’s request will stay in a pending state. Once Tab A's callback function resolves (or the tab crashes), the browser automatically hands the lock to the next in line.

Solving the Token Refresh Storm

Let’s look at a practical implementation of that token refresh problem. We want only one tab to perform the refresh, while the others wait and then use the newly acquired token.

async function getValidToken() {

const token = localStorage.getItem('auth_token');

if (!isExpired(token)) {

return token;

}

// Use a lock to ensure only one tab refreshes

return await navigator.locks.request('auth_token_refresh', async () => {

// Re-check expiration inside the lock!

// Another tab might have finished the refresh while we were waiting.

const latestToken = localStorage.getItem('auth_token');

if (!isExpired(latestToken)) {

return latestToken;

}

console.log("This tab is refreshing the token...");

const newToken = await api.refreshPath();

localStorage.setItem('auth_token', newToken);

return newToken;

});

}This pattern is a game changer. The "re-check" inside the lock is the most important part. Because the lock request is asynchronous, the state of the world might have changed by the time you actually acquire it. This is a classic "Double-Checked Locking" pattern adapted for the web.

Shared vs. Exclusive Locks

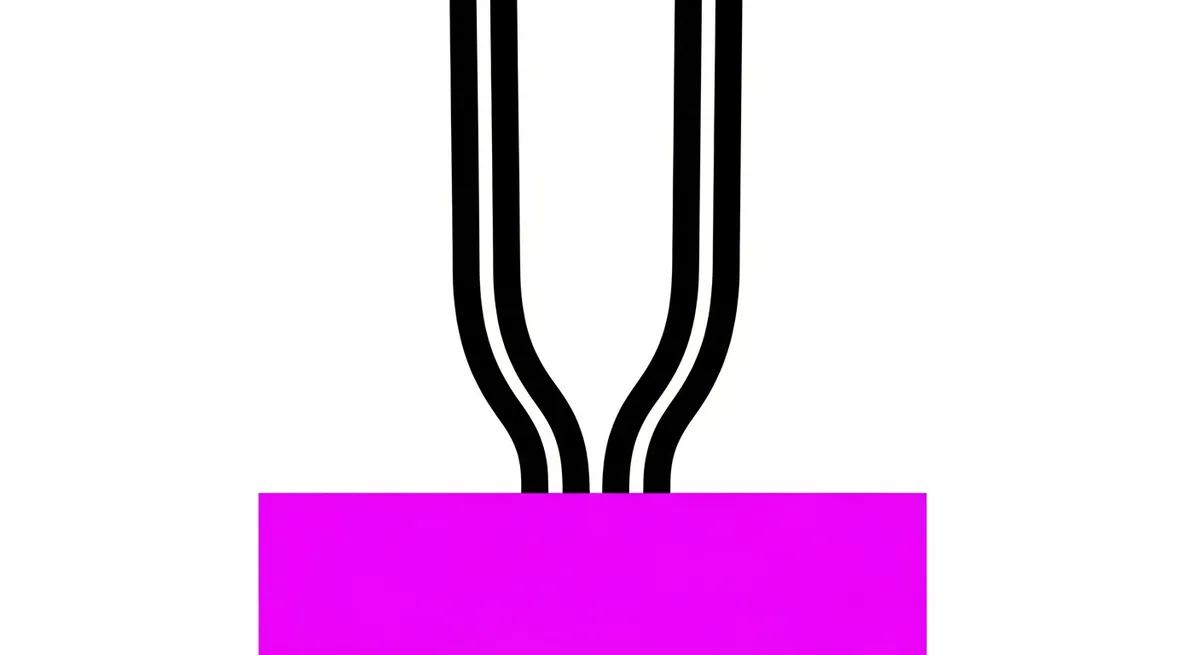

By default, locks are exclusive. Only one requester can hold it. But sometimes that’s too restrictive.

Suppose you have a complex IndexedDB structure. You want many tabs to be able to *read* from it simultaneously to render the UI, but if one tab starts a *write* operation (like a database migration or a heavy sync), all reads should pause until the write is done.

The Web Locks API handles this with the mode option:

// Reading data (Shared)

async function readData() {

await navigator.locks.request('db_sync', { mode: 'shared' }, async (lock) => {

const data = await db.getAll('tasks');

renderUI(data);

});

}

// Writing data (Exclusive)

async function writeData(changes) {

await navigator.locks.request('db_sync', { mode: 'exclusive' }, async (lock) => {

// No other 'shared' or 'exclusive' locks can be held right now.

await db.put('tasks', changes);

});

}- Shared locks can be held by multiple tabs at once.

- Exclusive locks can only be held by one tab, and only if no other locks (shared or exclusive) are held for that resource.

This mirrors how professional-grade databases handle concurrency. If you're building a local-first app, you should probably be wrapping your IndexedDB transactions in shared locks by default.

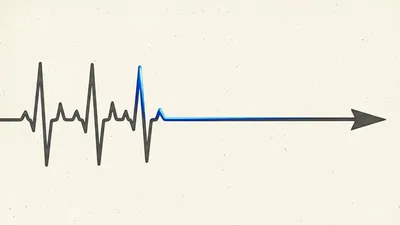

What Happens if a Tab Crashes?

This is where manual localStorage locks fail miserably. If you set a is_locked flag in storage and the user closes the tab or the browser crashes, that flag stays true forever. Your app is now deadlocked.

The Web Locks API is managed by the browser process itself. If the tab holding a lock is terminated, the lock is automatically released. There is no "stale lock" problem. The browser knows the execution context is gone and cleans up the queue.

However, you still have to worry about your own code hanging. If your async function never resolves (maybe a fetch request that never timeouts), you’ll hold that lock forever within that session.

// A safer way to handle timeouts

const controller = new AbortController();

const timeoutId = setTimeout(() => controller.abort(), 5000);

try {

await navigator.locks.request('resource', { signal: controller.signal }, async (lock) => {

// Perform work

});

} catch (err) {

if (err.name === 'AbortError') {

console.error("Failed to acquire lock within 5 seconds");

}

} finally {

clearTimeout(timeoutId);

}The "If Available" Pattern

Sometimes you don't want to wait. If a background sync process is already running in another tab, your current tab doesn't need to queue up; it should just give up and try again later.

The ifAvailable option allows you to attempt to grab a lock without blocking.

await navigator.locks.request('cleanup_task', { ifAvailable: true }, async (lock) => {

if (!lock) {

console.log("Another tab is already cleaning up. I'll skip it.");

return;

}

// We got the lock!

await performCleanup();

});If the lock isn't immediately available, the callback is invoked with null instead of a lock object. This is perfect for non-essential background tasks that shouldn't stack up.

Debugging the Ghost: navigator.locks.query()

One of the hardest parts of concurrency is visibility. Why is my app hanging? Is Tab A holding the lock?

The API provides a introspection method: navigator.locks.query(). You can run this in your dev console to see exactly what’s happening across all tabs.

const state = await navigator.locks.query();

console.log(state);This returns a snapshot of all held and requested locks in the current origin. It shows you:

1. Held locks: Which tab (clientId) has it, the mode, and the name.

2. Pending requests: Which tabs are waiting in the queue.

If you see a long queue for a specific resource, you know exactly where your bottleneck is.

Real-World Gotcha: Deadlocks

Even with a clean API, you can still shoot yourself in the foot. The most common way is via Deadlocks.

Imagine Tab A requests Lock 1, then while holding it, tries to request Lock 2.

Meanwhile, Tab B holds Lock 2 and tries to request Lock 1.

Neither tab can proceed. They will wait forever.

// DO NOT DO THIS

await navigator.locks.request('lock_1', async () => {

await navigator.locks.request('lock_2', async () => {

// Complex logic

});

});To avoid this, always acquire locks in a consistent order throughout your application. If you always request lock_1 before lock_2, a deadlock is impossible.

Another subtle gotcha is re-entrancy. Web Locks are not re-entrant. If you hold a lock and then call a function that tries to request the *same* lock, your code will hang.

async function outer() {

await navigator.locks.request('my_lock', async () => {

await inner();

});

}

async function inner() {

// This will hang forever because 'my_lock' is already held by this tab!

await navigator.locks.request('my_lock', async () => {

// ...

});

}Performance Considerations

You might be wondering if this adds significant overhead. The answer is: not really.

The communication happens via the browser's IPC (Inter-Process Communication). It's much faster than any hacky solution involving polling localStorage or IndexedDB. However, you shouldn't use locks for high-frequency operations. If you're trying to lock a resource 1,000 times per second during a mouse-move event, you're going to see performance degradation.

Locks are for coarse-grained coordination. Use them for database transactions, network requests, or complex state reconciliations.

Integrating with State Management

If you're using something like Redux, Zustand, or TanStack Query, where should the locks live?

In my experience, locks belong in the Layer of Truth. If your Layer of Truth is a remote API, the lock should surround the fetch/mutation logic. If your Layer of Truth is IndexedDB (as in a local-first app), the lock should surround the database repository logic.

For example, a custom hook for a local-first app might look like this:

function useUpdateTask() {

return async (taskId, updates) => {

return await navigator.locks.request('tasks_db', async () => {

const task = await db.tasks.get(taskId);

const merged = { ...task, ...updates, updatedAt: Date.now() };

await db.tasks.put(merged);

// Notify other tabs via BroadcastChannel if necessary

bc.postMessage({ type: 'TASK_UPDATED', id: taskId });

});

};

}Browser Support and Polyfills

As of 2024, the Web Locks API is supported in all major evergreen browsers (Chrome, Edge, Firefox, and Safari). It’s been stable for a while.

If you need to support truly ancient browsers, there are polyfills available, but they usually fall back to localStorage polling, which loses the "auto-release on crash" benefit. If you’re building modern web apps, you can likely use the native API without fear.

Final Thoughts

We spend a lot of time thinking about how to sync data between the client and the server, but we often neglect the sync between the client and... itself.

The "Ghost in the Second Tab" is a byproduct of the modern web's power. We aren't building static pages anymore; we're building distributed systems that happen to run in a browser. The Web Locks API is the most robust way to ensure those systems don't trip over each other.

Next time you find yourself writing a complex useEffect to handle storage events or wondering why your database is corrupted when two tabs are open, stop. Don't reach for a complex event-driven architecture. Reach for navigator.locks. It’s the closest thing we have to a "don't break everything" button for multi-tab applications.

Stop letting your tabs fight. Give them a referee.