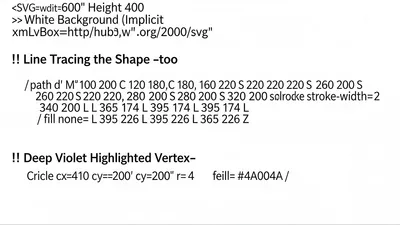

Monomorphism Is the Secret to Speed

Understanding how JavaScript engines use hidden classes and inline caches to optimize your code is the key to writing truly high-performance applications.

I spent three days once staring at a profiler, trying to figure out why a single function in our rendering loop was dragging the entire frame rate into the dirt. On paper, it was a simple property access—just a user.id lookup—but the V8 engine was treating it like a complex cryptographic puzzle. That was my first real encounter with the "performance cliff" of megamorphism, and it changed how I look at JavaScript objects forever.

We’re taught that JavaScript is a dynamic, "anything goes" language where objects are just loose bags of properties. You can add a key here, delete a key there, and change a string to a number whenever you feel like it. While that's technically true for the programmer, it’s a nightmare for the engine. To make your code fast, modern JavaScript engines like V8 (Chrome/Node), SpiderMonkey (Firefox), and JavaScriptCore (Safari) try to treat your dynamic objects as if they were rigid, static structures.

This optimization trick is built on two pillars: Hidden Classes and Inline Caches. And the secret to keeping them happy is a concept called Monomorphism.

The Illusion of the Hash Map

If you ask a developer what a JavaScript object is, they’ll likely say "it’s a hash map." It maps a string key to a value. In theory, looking up a key in a hash map is $O(1)$. But $O(1)$ doesn't mean "fast"—it just means "constant time." Calculating a hash, handling collisions, and digging through a bucket in memory is actually quite slow when you're doing it millions of times per second inside a hot loop.

C++ or Rust don't have this problem with their objects (structs or classes). When you compile a C++ program, the compiler knows exactly where every property is located in memory relative to the start of the object. It’s just a fixed offset. object + 8 bytes is the ID; object + 16 bytes is the name.

JavaScript engines want that C++ speed. To get it, they invent Hidden Classes (sometimes called Shapes or Maps).

How Hidden Classes are Born

Every time you create an object, the engine assigns it a hidden class. If two objects share the same structure, they share the same hidden class.

const userA = { name: "Alice", age: 30 };

const userB = { name: "Bob", age: 25 };In this case, userA and userB share the same hidden class. The engine says: "Okay, any object with this specific hidden class has name at offset 0 and age at offset 1."

However, the order of property assignment matters. This is where people usually start breaking their performance without realizing it.

const userC = {};

userC.name = "Charlie";

userC.age = 40;

const userD = {};

userD.age = 40; // Oops, different order

userD.name = "Dan";To us, userC and userD look identical. To V8, they are completely different. userC follows a transition path of Empty -> Name -> Age, while userD follows Empty -> Age -> Name. They end up with two different hidden classes, and the engine can no longer treat them as the same "type."

The Magic of Inline Caches (IC)

Hidden classes are only half of the story. The real speed comes from Inline Caching.

Imagine you have a function that calculates a total:

function getPrice(item) {

return item.price;

}The first time getPrice is called with an object, the engine looks at the object's hidden class. It finds that price is at offset 2. The engine then "optimizes" the function by literally writing a note into the machine code: "If the hidden class of item is Class_123, the value is at offset 2."

The next time you call getPrice with the same type of object, the engine doesn't search for the property. It just checks: "Is this Class_123? Yes? Okay, grab the value at offset 2."

This is Monomorphism. The function has only ever seen one "shape" of object. It is specialized, lightning-fast, and can even be inlined directly into the calling code.

When Things Get Messy: Polymorphism

If you start passing different kinds of objects to that same function, you force the engine to work harder.

function getPrice(item) {

return item.price;

}

const book = { price: 10, title: "Hitchhiker's Guide" };

const car = { brand: "Tesla", price: 50000 }; // Price is in a different 'position'

getPrice(book); // IC becomes Monomorphic

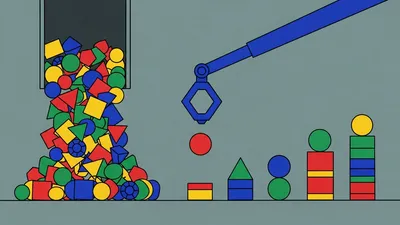

getPrice(car); // IC becomes PolymorphicNow, the Inline Cache for getPrice has to store a list:

1. If shape is BookShape, offset is 0.

2. If shape is CarShape, offset is 1.

This is Polymorphism. The engine now has to perform a check (a "stub search") against a list of known shapes. It’s still relatively fast if the list is small (usually up to 4 shapes), but it’s slower than the single-check monomorphic case.

The Performance Cliff: Megamorphism

If you keep passing different shapes to the same function, the engine eventually gives up. It can't keep an infinite list of shapes in the Inline Cache. Once you pass more than a handful of different shapes (usually 5 or more), the function becomes Megamorphic.

At this point, the engine stops trying to be clever. It throws away the specialized machine code and reverts to a generic, slow hash-map lookup.

I’ve seen "generic" utility functions in large codebases—things like getProperty(obj, key)—that are used across the entire app. These functions are almost always megamorphic. If that function is in a tight loop, you are paying a massive performance tax on every single iteration.

Real-World Examples of Breaking Monomorphism

It's easier to break monomorphism than you think. Here are the most common ways I see developers accidentally tanking their performance.

1. Inconsistent Initialization Order

As shown earlier, the order in which you assign properties creates different hidden classes. The fix is simple: always initialize your properties in the constructor or use a consistent object literal.

Bad:

function createPoint(x, y, z) {

const p = {};

p.x = x;

if (z) p.z = z;

p.y = y;

return p;

}Good:

function createPoint(x, y, z) {

return {

x: x,

y: y,

z: z // Always include z, even if it's null/undefined

};

}2. Adding Properties Later

When you add a property to an object after it's been created, you trigger a "transition" to a new hidden class. If you do this sporadically, you end up with a tree of hidden classes that makes it hard for the engine to optimize.

Avoid this:

const user = { name: "John" };

// ... later ...

user.admin = true;Instead, define the full shape upfront. Even admin: false is better than adding the key later.

3. The delete Keyword

delete is the nuclear option for performance. When you delete a property from an object, you often kick the object out of the "fast path" entirely. The engine realizes that the fixed-offset model is too hard to maintain for an object that can lose properties at any time, and it turns the object into "dictionary mode" (a slow hash map).

If you need to "remove" a property, set it to undefined or null.

const obj = { a: 1, b: 2 };

// delete obj.a; // DON'T DO THIS

obj.a = undefined; // DO THIS4. Array of "Mixed" Objects

This is a subtle one. If you have an array where the objects have slightly different shapes, iterating over that array and passing each element to a function will turn that function polymorphic or megamorphic.

const items = [

{ id: 1, type: 'a' },

{ type: 'b', id: 2 }, // Different shape!

{ id: 3, type: 'c', extra: true } // Different shape!

];

items.forEach(item => processItem(item)); // processItem becomes polymorphicHow to Profile This

You might be wondering: "How do I know if my code is megamorphic?"

If you're using Node.js, you can use the --trace-ic flag to see what’s happening under the hood. It produces a log file that can be analyzed with tools like IC Explorer.

Alternatively, you can use the v8-natives package in a development environment to check the status of a function:

// This only works if you run Node with --allow-natives-syntax

const status = %GetOptimizationStatus(myFunction);

// There are specific bitmasks to check for monomorphic vs polymorphicBut usually, you don't need to go that deep. If you follow the "always use the same shape" rule, you'll be ahead of 99% of JavaScript developers.

The "Classes" vs "Object Literals" Debate

There is a common misconception that using the class keyword automatically makes your code faster. It's not the class keyword itself that's magical; it's the fact that classes encourage a fixed shape.

When you use a constructor, you typically assign all properties in the same order every time.

class Player {

constructor(name, score) {

this.name = name;

this.score = score;

}

}

const p1 = new Player("A", 10);

const p2 = new Player("B", 20);V8 sees p1 and p2 and knows with 100% certainty they share the same hidden class. Object literals {} are just as fast *if* you are disciplined about the key order and presence. Classes just make that discipline the default.

Is This Premature Optimization?

I can hear the "clean code" advocates already: "Isn't this worrying about internals that don't matter?"

In many cases, yes. If you’re writing a React component that renders once every few seconds, you don't need to worry about monomorphism. But if you are writing:

- A data processing library

- A physics engine

- A custom state management system

- A high-frequency event handler

- A library used by thousands of other developers

...then this is the difference between your code feeling "snappy" and your code feeling "bloated."

The overhead of a megamorphic call isn't just the hash lookup; it's the fact that the engine cannot inline the function. Inlining is the holy grail of compiler optimization. If the engine knows exactly what a function does, it can pull that logic directly into the loop, eliminating the overhead of the function call entirely. Megamorphism creates a "wall" that the optimizer cannot see through.

The Practical Takeaway

Writing high-performance JavaScript isn't about using complex algorithms; it's about making your code predictable for the engine.

1. Initialize all properties in your constructors. Don't wait until later.

2. Never change the order of properties.

3. Avoid `delete`.

4. Keep your "hot" functions monomorphic. If a function is called millions of times, ensure the objects passed to it always have the same hidden class.

The JavaScript engine is a incredibly sophisticated piece of engineering designed to turn your messy, dynamic code into lean machine instructions. When you write monomorphic code, you're not just "writing fast code"—you're finally letting the engine do the job it was built to do.

Next time you see a function that should be fast but isn't, stop looking at the logic. Look at the shapes of the data you're feeding it. The secret to speed is often hiding in plain sight, right in the structure of your objects.