The Structured Clone Tax: Why Your Web Worker Communication is Slower Than You Think

Discover why the default way we send data to Web Workers is quietly killing your performance and how to implement true shared memory with Atomics.

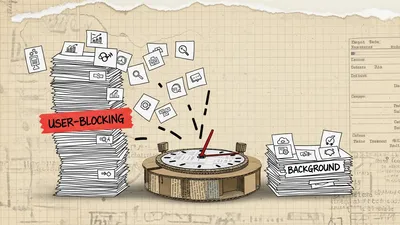

You’ve got a 50MB JSON object representing a complex 3D scene or a massive data grid. To keep your UI responsive, you do the "responsible" thing: you spin up a Web Worker and postMessage(bigData) it over. You expect the main thread to stay buttery smooth while the worker crunches the numbers. Instead, the UI stutters for 100ms. The culprit isn't the computation; it's the delivery fee.

In the JavaScript world, we call this the Structured Clone Tax.

When you send data via postMessage, the browser doesn't just pass a pointer. It performs a deep copy of the entire object graph. It traverses every property, handles cyclic references, preserves types like Map, Set, and Date, and recreates that entire structure in the memory space of the target worker. For small messages, it’s negligible. For large datasets or high-frequency updates (like 60fps game state), it is a silent performance killer.

The Anatomy of a Clone

The Structured Clone Algorithm is remarkably robust, but it is not magic. It’s essentially a high-performance, internal serialization format. If you send an object with 10,000 nodes, the browser has to visit 10,000 nodes, allocate memory for 10,000 new nodes, and copy the values over.

Here is a quick way to visualize the "Tax" in your own console:

const size = 1_000_000;

const bigData = new Array(size).fill(0).map((_, i) => ({ id: i, value: Math.random() }));

const start = performance.now();

// Simulating the internal work of postMessage

const clone = structuredClone(bigData);

const end = performance.now();

console.log(`Cloning ${size} objects took ${end - start}ms`);On a modern MacBook, cloning a million-item array of objects can take anywhere from 80ms to 200ms. During that time, the main thread—the thread responsible for your CSS animations, scroll events, and button clicks—is blocked. You didn't offload the work; you just delayed it.

Transferables: The Partial Solution

Before we get to the real "shared memory" solution, we have to acknowledge Transferable Objects. If your data is a TypedArray (like Uint8Array) or an ArrayBuffer, you can "transfer" ownership.

const buffer = new Uint8Array(1024 * 1024 * 50).buffer; // 50MB

worker.postMessage(buffer, [buffer]);

console.log(buffer.byteLength); // 0This is nearly instantaneous because the browser just moves a reference in the memory management system. However, there is a catch: it is destructive. Once you transfer an ArrayBuffer, it becomes neutered in the original thread. You can't read from it. You can't write to it. If you need both threads to see the data simultaneously, Transferables won't help you.

SharedArrayBuffer: True Zero-Copy

If you want to kill the Structured Clone Tax entirely, you need shared memory. This is where SharedArrayBuffer (SAB) comes in. Unlike a standard ArrayBuffer, a SharedArrayBuffer points to a chunk of memory that can be mapped into the memory space of multiple agents (the main thread and multiple workers) at the same time.

No copying. No transferring. No tax.

// Main Thread

const sharedBuffer = new SharedArrayBuffer(1024); // 1KB of shared memory

const uint8 = new Uint8Array(sharedBuffer);

uint8[0] = 42;

worker.postMessage(sharedBuffer); // We still postMessage, but we only send the *reference*Now, the worker receives the same buffer. If the worker changes uint8[0] to 100, the main thread sees 100 immediately.

The Security Elephant in the Room

You might remember SharedArrayBuffer being disabled for a long time. This was due to Spectre and Meltdown, side-channel attacks that used high-resolution timers to steal data. To use SharedArrayBuffer today, your server must serve specific headers to opt into "Cross-Origin Isolation":

1. Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy: same-origin

2. Cross-Origin-Embedder-Policy: require-corp

Without these, window.SharedArrayBuffer will be undefined. It's a hoop to jump through, but for high-performance applications, it's the only way forward.

The Chaos of Unsynchronized Memory

Shared memory is a double-edged sword. In standard JavaScript, we rarely worry about race conditions because only one thing happens at a time on the main thread. With SharedArrayBuffer, we enter the world of true multi-threaded concurrency.

Imagine this scenario:

1. Thread A reads uint8[0] (value is 10).

2. Thread B reads uint8[0] (value is 10).

3. Thread A adds 1 and writes 11 back to uint8[0].

4. Thread B adds 1 and writes 11 back to uint8[0].

We performed two increments, but the value is 11, not 12. This is a classic Race Condition.

Enter Atomics

To solve this, we don't use standard assignment (=) or math operators. We use the Atomics object. Atomics ensures that operations are "atomic"—they happen as a single, indivisible unit that cannot be interrupted by another thread.

Let's fix that increment problem:

// Instead of uint8[0]++

Atomics.add(uint8, 0, 1);Atomics.add guarantees that the read-modify-write cycle happens safely. No matter how many workers are hitting that same memory address, the count will be accurate.

Beyond Simple Math: Signaling with Wait and Notify

The real power of Atomics isn't just in safe math; it's in thread synchronization. If your worker is waiting for the main thread to finish preparing a batch of data, you don't want the worker to run a while(true) loop (busy-waiting), which eats 100% CPU. You want the worker to sleep until the data is ready.

Atomics.wait() and Atomics.notify() are your tools here.

A Practical Example: The Worker Signal

Here is a pattern I use for a high-performance worker that waits for a "Go" signal from the main thread.

The Worker (`worker.js`):

self.onmessage = (event) => {

const sharedBuffer = event.data;

const sharedArray = new Int32Array(sharedBuffer);

console.log("Worker: Waiting for signal...");

// Atomics.wait(typedArray, index, expectedValue)

// This blocks the worker thread until the value at index 0 is NO LONGER 0

Atomics.wait(sharedArray, 0, 0);

console.log("Worker: Signal received! Starting work...");

// Do heavy processing here

};The Main Thread:

const sharedBuffer = new SharedArrayBuffer(1024);

const sharedArray = new Int32Array(sharedBuffer);

const worker = new Worker('worker.js');

worker.postMessage(sharedBuffer);

// Simulate some prep work

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("Main: Work is ready, signaling worker.");

// Change the value

Atomics.store(sharedArray, 0, 1);

// Wake up one worker waiting on index 0

Atomics.notify(sharedArray, 0, 1);

}, 2000);Note: You cannot use Atomics.wait on the main thread. The browser will throw an error. This is intentional; blocking the main thread would freeze the UI, defeating the whole purpose of using workers.

Designing a Shared State System

If you're moving away from Structured Clone to Shared Memory, you have to change how you think about your data structures. You can't just put a JavaScript object into a SharedArrayBuffer. You have to deal with raw bytes.

This usually means defining a Schema.

If you have a list of players in a game, you might define a fixed-size block for each player:

- Bytes 0-3: Player ID (Int32)

- Bytes 4-7: X Position (Float32)

- Bytes 8-11: Y Position (Float32)

- Bytes 12-15: Health (Int32)

const PLAYER_SIZE = 16; // 16 bytes per player

const MAX_PLAYERS = 100;

const buffer = new SharedArrayBuffer(MAX_PLAYERS * PLAYER_SIZE);

// Helper to access player data

function getPlayerView(buffer, index) {

const offset = index * PLAYER_SIZE;

return {

id: new Int32Array(buffer, offset, 1),

pos: new Float32Array(buffer, offset + 4, 2),

health: new Int32Array(buffer, offset + 12, 1)

};

}This feels like a step backward into the world of C or C++. It’s more manual. It’s more error-prone. But the performance gains are massive. You can update 10,000 player positions in a worker and read them on the main thread for rendering with zero serialization overhead.

The Complexity Tax

Why doesn't everyone use SharedArrayBuffer? Because the "tax" isn't gone; it's just shifted from the CPU to the Developer.

1. Memory Management: You have to manage your own memory offsets. If you overwrite a byte by mistake, you get corrupted data, not a clean JS error.

2. Strings are Hard: Strings in JS are UTF-16 and dynamically sized. To put them in a SharedArrayBuffer, you have to encode them to Uint8Array using TextEncoder and ensure you have enough pre-allocated space.

3. No Garbage Collection: Data in a SharedArrayBuffer is not garbage collected by the JS engine like normal objects. If you "delete" a player, you just mark those bytes as "available" for reuse.

When should you actually do this?

Don't go rewriting your entire Redux store into a SharedArrayBuffer tomorrow. Most applications don't need this level of optimization.

Use Structured Clone if:

- You are sending data occasionally (e.g., after a fetch request).

- Your data structures are deeply nested and highly dynamic.

- You aren't seeing frame drops on the main thread during postMessage.

Use SharedArrayBuffer if:

- You are building a game engine, a video editor, or a heavy data visualization tool.

- You need to sync state between threads at 60fps.

- You are working with massive datasets (10MB+) that need to be accessed by multiple workers simultaneously.

- You are porting C++ code via WebAssembly (Wasm uses SABs for its linear memory when multi-threading is enabled).

The Middle Ground: Comlink and abstractions

If you want the benefits of Workers without the clunky postMessage syntax, look at libraries like Comlink by Google. It wraps postMessage in a Proxy-based API that feels like calling methods on a local object. While Comlink still uses Structured Clone under the hood, it makes the architectural transition to workers much easier. Once you have a worker-based architecture, you can then surgically replace hot paths with SharedArrayBuffer.

Final Thoughts

The Structured Clone Tax is a reminder that there is no such thing as a free abstraction. postMessage is easy because it handles the hard work of isolation for you. But isolation has a cost.

If you find your application stuttering while your "background" worker is supposed to be doing the heavy lifting, take a look at your message sizes. You might be paying a much higher tax than you realized. By switching to SharedArrayBuffer and Atomics, you're essentially choosing to handle the synchronization yourself in exchange for raw, uncompromised performance.

It’s a move from the "Managed" world to the "System" world, and in the modern web, it’s often the only way to squeeze every drop of power out of the browser.