How to Implement Zstandard Compression Without Leaving Your Legacy Users in the Dark

Move beyond Brotli and learn how to leverage the newest browser compression standard to slash your API payload sizes while maintaining a seamless fallback strategy.

I was debugging a particularly bloated analytics endpoint last month when I realized we were spending more CPU cycles on compression than on the actual database query. Brotli was our go-to for static assets, but on dynamic API responses, it felt like we were trading one bottleneck for another.

For years, the web has been locked in a duopoly between the ubiquitous Gzip and the high-performance-but-slow-to-compress Brotli. But the landscape changed recently. With Chrome 123, Zstandard (zstd) officially entered the browser arena, promising the compression ratios of Brotli with the blistering speed of Gzip.

The problem is that you can’t just flip a switch and assume every client knows what a .zst stream is. If you do, you’ll be serving unreadable binary junk to anyone on an older browser or a non-updated mobile app. Here is how to navigate the transition to Zstandard without breaking your site for the "legacy" crowd—which, in this context, is basically anyone who hasn't updated their browser in the last six months.

Why Bother with Zstandard?

The short answer is efficiency. Zstandard was developed by Yann Collet at Meta, and it’s a bit of a freak of nature. It uses a technique called Finite State Entropy (FSE), which is a faster way to handle the coding stage of compression.

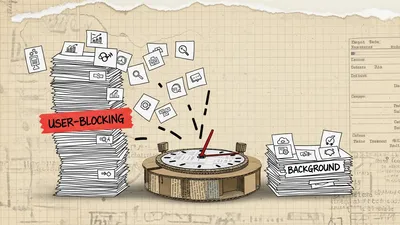

In the real world of API development, we care about two things: Latency (how fast the user gets the data) and Throughput (how much data we can shove through the pipe).

1. Gzip is fast but has mediocre compression ratios.

2. Brotli has incredible compression ratios but is notoriously slow to compress on the fly (level 4-6 is the sweet spot, but anything higher kills your server CPU).

3. Zstandard sits in the middle. It often matches Brotli’s compression for JSON payloads while being significantly faster than even Gzip.

If your API returns large JSON objects—think product catalogs, geo-data, or massive state blobs—Zstandard is a massive win for your infrastructure costs and your user's battery life.

The Content-Encoding Handshake

Everything in the world of web compression relies on the Accept-Encoding request header. When a browser makes a request, it shouts a list of algorithms it understands.

A modern Chrome request might look like this:Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br, zstd

If you see zstd in that list, you're clear for takeoff. If you don't, you have to fall back to br (Brotli) or gzip. The key to a "no-darkness" strategy is the negotiation logic on your backend or edge.

Implementation: The Middleman Strategy

Let’s look at a Node.js example. Most people use a library like compression, but that hasn't caught up to Zstd natively in every environment yet. We’ll build a small middleware logic to show how the selection process works.

const zstd = require('node-zstd'); // Or any zstd binding

const zlib = require('zlib');

function getCompressionPreference(acceptEncoding) {

if (!acceptEncoding) return null;

// We want to prioritize zstd if available

if (acceptEncoding.includes('zstd')) {

return 'zstd';

} else if (acceptEncoding.includes('br')) {

return 'br';

} else if (acceptEncoding.includes('gzip')) {

return 'gzip';

}

return null;

}

// In your Express middleware

app.use((req, res, next) => {

const encoding = getCompressionPreference(req.headers['accept-encoding']);

if (!encoding) return next();

const originalWrite = res.write;

const originalEnd = res.end;

let chunks = [];

// Capture the output to compress it later (Simplified for demonstration)

res.write = (chunk) => chunks.push(chunk);

res.end = (chunk) => {

if (chunk) chunks.push(chunk);

const buffer = Buffer.concat(chunks);

if (encoding === 'zstd') {

res.setHeader('Content-Encoding', 'zstd');

zstd.compress(buffer, (err, result) => {

res.setHeader('Content-Length', result.length);

originalEnd.call(res, result);

});

} else if (encoding === 'br') {

res.setHeader('Content-Encoding', 'br');

zlib.brotliCompress(buffer, (err, result) => {

originalEnd.call(res, result);

});

} else {

// Fallback to Gzip

res.setHeader('Content-Encoding', 'gzip');

zlib.gzip(buffer, (err, result) => {

originalEnd.call(res, result);

});

}

};

next();

});The logic here is simple: we look at what the user *can* do, and we pick the best option. If they don't support zstd, they get br. If they don't support br, they get gzip. No one is left in the dark.

Configuring Nginx for the Modern Era

Most of us aren't compressing things inside the application code (and we shouldn't be, if we can avoid it). We usually offload this to Nginx or a CDN.

To get Zstd working in Nginx, you'll likely need the ngx_http_zstd_module. It isn't always in the main distribution yet, so you might have to compile Nginx with the module or use a distribution like OpenResty that supports it more readily.

Here is what a robust Nginx config looks like that handles the hierarchy:

http {

# Gzip settings (The reliable fallback)

gzip on;

gzip_types text/plain application/json application/javascript text/css;

gzip_proxied any;

# Brotli settings (The mid-tier)

brotli on;

brotli_comp_level 5;

brotli_types text/plain application/json application/javascript text/css;

# Zstandard settings (The elite tier)

zstd on;

zstd_level 3; # Level 3 is the standard balance of speed/ratio

zstd_types text/plain application/json application/javascript text/css;

server {

listen 443 ssl;

# ... your other config ...

location /api/v1/ {

proxy_pass http://api_backend;

# Crucial: Ensure the cache knows the response depends on the encoding

add_header Vary "Accept-Encoding";

}

}

}The "Vary" Header is Non-Negotiable. I've seen teams implement compression and then wonder why their users are getting gibberish. If you don't include Vary: Accept-Encoding, a CDN or a local cache might store the Zstd version and serve it to a Safari user who only understands Gzip. That’s how you leave users in the dark.

The Dictionary Advantage (Advanced Mode)

Zstandard’s real "killer feature" is support for dictionaries.

Imagine you’re sending small JSON objects that look like this: {"id": 102, "type": "user_action", "timestamp": "2023-10-27T10:00:00Z", "status": "success"}

In a standard compression stream, the algorithm has to learn that "type": "user_action" repeats over and over. With a dictionary, you "pre-train" the algorithm on your common JSON keys and values.

You can create a dictionary from your API logs:

zstd --train-full logs/*.json -o api_dictionary.zstdCurrently, browser support for Shared Dictionary Compression (SDR) is in the "Origin Trial" phase and experimental flags. It allows the browser to cache that api_dictionary.zstd file and use it to decompress all future API calls. This can shrink your payloads by an additional 40-60% compared to standard compression because the algorithm doesn't have to transmit the "shape" of your data—only the data itself.

Measuring Success (and Failure)

Don't take my word for it. You need to see the numbers. If you’re implementing this, you should be tracking response_size and compression_time across your different encodings.

If you’re using something like Prometheus and Grafana, I highly recommend tagging your metrics with the encoding used:

// Pseudo-code for tracking

const start = process.hrtime();

// ... compression happens ...

const end = process.hrtime(start);

metrics.histogram('api_compression_duration_ms', end[1] / 1000000, {

encoding: encodingType,

endpoint: req.path

});What I’ve found in my own testing is that Zstd level 3 is almost always faster than Brotli level 4 while yielding a smaller file size for dynamic JSON. For static files (CSS/JS), Brotli at level 11 still usually wins on file size, but since you’re pre-compressing those anyway, the CPU time doesn’t matter.

Common Gotchas

1. The Proxy Problem

Cloudflare and other major CDNs have started rolling out Zstd support, but they don't all support it on the "ingress" side (from your origin to the CDN). If you're compressing with Zstd at your origin, make sure your CDN is configured to pass that through or re-compress it appropriately. If the CDN doesn't understand Zstd, it might strip the header or, worse, try to Gzip the already compressed Zstd binary.

2. The CPU Trade-off

While Zstd is efficient, compressing everything consumes CPU. If your server is already at 90% CPU utilization, adding *any* compression might be the straw that breaks the camel's back. In those cases, offloading compression to your load balancer or a sidecar process is a better move.

3. Client-Side Libraries

If you’re working in a non-browser environment (like a React Native app or a legacy Java service), don't assume the HTTP client handles Zstd. You may need to manually add a decompressor.

// Example: Fetching zstd data in a custom environment

import { decompress } from 'zstd-codec';

async function fetchZstd(url) {

const response = await fetch(url);

const arrayBuffer = await response.arrayBuffer();

if (response.headers.get('Content-Encoding') === 'zstd') {

return decompress(new Uint8Array(arrayBuffer));

}

return arrayBuffer;

}Where do we go from here?

Zstandard isn't just a marginal improvement; it's a structural shift in how we handle data over the wire. We are moving toward a web where the overhead of JSON's verbosity is almost entirely mitigated by intelligent, dictionary-aware compression.

The roadmap for most teams should look like this:

1. Audit your current traffic. If 70% of your users are on modern Chrome/Edge, you're leaving performance on the table by not using Zstd.

2. Enable Zstd with a robust fallback. Use Nginx or a modern middleware to ensure Accept-Encoding is respected.

3. Monitor the `Vary` header. Ensure your infrastructure isn't poisoning its own cache.

4. Watch Shared Dictionaries. This is the next frontier. Once this stabilizes, the "cost" of using JSON over a binary format like Protobuf will shrink even further.

Implementing Zstandard today is about more than just being on the bleeding edge. It’s about building a backend that is respectful of the user's data plan and the server's CPU cycles. And by following the negotiation patterns, you ensure that the person using a three-year-old iPhone still gets their data—just a few milliseconds slower than everyone else.